Nothing in Moderation

“Fuck,” I muttered as I opened my eyes, furious that I had woken at all. I didn’t want to wake up. I was over it. An aggressive, unforgiving, bright morning light was the last thing I felt like. There’s that moment just before your mind kicks into gear that you’re still oblivious to everything that plagued your mind before you went to sleep the night before. There’s that moment of peace. It’s very fleeting -- a couple of seconds before the reality of what being awake represents collides into your consciousness, and you are properly awake. There’s no point in trying to go back to sleep once this happens because the mind has already kicked into gear and all you can do is try to mitigate the panic, dread, and racing.Nothing in Moderation is Clinton Fein's first book scheduled for release in 2026.

My bedroom could fit nothing more than a double mattress and had no windows. I was both literally and metaphorically in the closet. Despite having tasted the freedom of expressing my homosexuality in Amsterdam, I wasn’t ready to come out, despite the rumors swirling around at home, from which I had raced away.

I managed to secure a retail job at Arise, a futon store on 72nd Street between Broadway and Amsterdam. At that point, I didn’t even know what a futon was. (It’s a foldable, spring-less, cotton mattress that originated in Japan.)

I was a natural salesman, and working two blocks from my Upper West Side apartment was relatively easy. I made just enough money to be able to pay for my tiny little room, although not much else. Even then, Manhattan was damn expensive.

My arrival in December exposed me to the freezing cold extremes of a New York winter. While I had visited New York as a teenager, nothing prepared me for this level of cold. Yet nothing could have been more exciting than being in a city that never sleeps. I didn’t sleep much either.

Spring in Central Park was spent lazing on the grass in Sheep’s Meadow, always passing by the Dakota on 72nd and Central Park West, where Yoko Ono lived and where John Lennon had been gunned down on my 16th birthday. Strolling down Columbus Avenue in cut-off denim and Reebok high tops (as was the fashion at the time), buying ice cream and burgers from Diane’s at 71st. Or shopping for clothes with Barbara at Trocadero on 67th, where she derived joy from buying me outfits I couldn’t afford.

Feasting on Mexican at Caramba!, where we would wolf down cheese enchiladas and chicken burrito combinations while downing margaritas. Or savoring the best quesadillas in the city. Before there were venti-size coffees at Starbucks, there were Caramba!’s Ridiculous sized slushy, frozen margaritas, where the prize for managing actually to finish one of these fishbowl-sized drinks was the chance to get even more fucked up on another.

As I had in Johannesburg, I would pretend to be straight to all the people I came into contact with through Barbara and Ben, date girls periodically, and always go out of my way to be the life of the party. The wild, wise guy who was too rebellious and ill-behaved to be gay. Too much of a player to have a steady girlfriend. Maintaining my façade.

When my friend, Matt Seegan, visited from South Africa, we would sit on my mattress in my little room smoking weed and cutting thumb-thick lines of cocaine before going out on the town to clubs like The Saint and Limelight and then stumble our way to 3 am after-parties at Save the Robots in Alphabet City, high as kites on ecstasy.

I led two lives, though.

The thing I loved more than anything else about Manhattan was the anonymity. Unlike Johannesburg, the likelihood of bumping into anyone I knew was slim to none. At night I would catch the 1, 2, or 3 train from the subway station at 72nd and Broadway, down to 14th Street in the West Village, where I discovered my favorite gay bar, Uncle Charlie’s, on Greenwich Avenue.

Uncle Charlie’s was a spacious two-roomed bar with video screens playing MTV music videos, drawing a crowded mix of suit-and-tie and jeans-and-t-shirt men.

Of all the shit ironies, as I came of age, so did fucking HIV and AIDS. At that point in time, seroconverting to HIV positive was considered a death sentence, and the George Herbert Bush Administration was not much better at dealing with AIDS than the Reagan Administration preceding it. The activist group started by Larry Kramer, ACT UP was in its prime. HIV messaging by gay organizations was primarily fear-based, with warnings about condoms — anywhere and everywhere sex was likely to happen. Gay sex and gay people were demonized outside big metropolis cities like New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco (even though San Francisco shuttered bathhouses in response to the epidemic), and homophobia in America was as rampant as it ever was during the worst days of apartheid in South Africa.

Despite being terrified of AIDS, I would pop into Uncle Charlie’s, nurse a beer or two, laser in on some hunk of a man, and before long, head to his place. The men were as buff and handsome as anyone I had ever perved over at High School, if not more. Uncle Charlie’s was renowned for it. I went home with someone every time I went there, which was frequent. It was like shooting fish in a barrel. With no cover charge, I was as happy to discover Uncle Charlie’s as I was when I discovered the three-story, gay bathhouse in Amsterdam.

I learned the language of the streets in the West Village (as well as the Meatpacking District bordering the West Side Highway, long before it became gentrified and trendy). It was gritty and edgy back then, with a tinge of danger, especially after 2 am. Furtive glances, lowered eyes, or a strategic nod communicated who was on the prowl, which would inevitably lead to quick, dirty sexual encounters wherever it was easiest, be it in an alley, public toilet, or a backroom of a seedy bar. Or in countless bedrooms in apartments all over the city.

It didn’t take me long to realize that this language was not restricted to gay bars and neighborhoods. On the subway, in the park, walking down Fifth Avenue, or simply sitting at the laundromat, there was always someone ready, willing, and able to engage in some form of sexual activity. We sure as hell didn’t need apps or cell phones.

Before Rudy Giuliani’s controversial reign as mayor and the Disneyfication of Times Square, 42nd Street was populated with many seedy video arcades and porn movie theaters, where it was easy to pick up men. All one needed for the arcades were poppers and tokens. And even tokens weren’t necessary. Men lurked in little booths with doors open, stroking their cocks or fingering their asses. One could stay and play, even go to someone’s car or apartment (if an encounter was especially rewarding), or simply shoot a load in the booth and head home.

In a dingy movie theater, the air thick with the aroma of amyl nitrates and bleach, one would sit on sticky, faux-leather seats within viewing distance of some man jacking off to Jeff Stryker or Joey Stefano looming large over the theater on a massive screen. Before you knew it, you were edging closer to one another and then jacking each other off. Or sucking each other off if the mood called for it. It left me feeling both filthy and exhilarated.

Being in the closet, however, meant never taking anyone home. Always on guard. Always having to pretend.

It was fucking exhausting.

I had been living in Los Angeles for about two years at that point. I met him at a nondescript dive bar called Gold Coast on Santa Monica Boulevard and La Jolla Avenue, directly across the road from the notorious Circus of Books. The gay scene around Fairfax and further to the east, was a much lower key, grittier affair then Micky’s, Rage, Revolver and all the other purple-neon-twink bars west of La Cienega that catered to the over-tanned, over-plucked, and over-waxed queens that populated the west end of West Hollywood. Lisa Vanderpump boys, long before there were Lisa Vanderpump boys.

Behind Gold Coast was the infamous Vaseline Alley, a very convenient pickup spot for those too trepidatious to venture into Circus of Books to loiter among cock rings, dildos and poppers, whilst surreptitiously browsing the porn magazines and DVDs. Cruising was rampant, whether you were horned up to the hilt, getting shitfaced bar hopping, or pretending to walk the dog. In spite of the “No Cruising” street signs, almost comically erected and summarily ignored.

The bars east of Fairfax were seedier, more authentic and frankly more my speed. With manlier men too. And in my mid-twenties prime, I had fortunately and fortuitously moved into an apartment on Orange Grove Avenue between Melrose and Beverly Boulevard — within easy walking distance of the cruisiest and sluttiest blocks of Santa Monica Boulevard.

I had wandered into Gold Coast for a drink and to assess the pickings for the evening, when I encountered a guy sitting alone at the bar nursing a drink. A couple of men were chatting in the back of the dimly lit bar, but it was pretty empty otherwise. Not that unusual for a school night. Had it been empty, I would have picked up yet another bloke pretending to page through magazines at Circle of Books or signaled to one of the cars cruising Vaseline Alley, and that would have been that. Getting laid that night was preordained. Getting laid any night around there was.

We began chatting, and he introduced himself. Joe Cannizzaro was a fashion designer who occupied a studio near Robertson Boulevard and Melrose Avenue. In the course of our back and forth, I told Joe I was looking to break into the movie industry. I was sick and tired of my retail job, despite the perks. I was managing Aaron Brothers on La Brea, one in a chain of framing and art supplies stores in California. The CEO of the chain was a former South African Breweries executive, Ron Cohen — the father of one of my best friends — who had lined up the job for me. And had graciously made me an Assistant Manager from the get-go after a precursory amount of training.

Nepotism and privilege notwithstanding, I didn’t enjoy servicing the entitled people I had to kiss up to, and I desperately wanted something more for myself. That’s what Los Angeles was all about, anyway. If you weren’t in “the industry” (you didn’t even need to specify which industry), it was only because you hadn’t made it yet.

After liquoring me up with a series of double vodka tonics, Joe casually mentioned that he knew someone who worked at Orion Pictures. That he would be happy to set up an interview. And did I want to go home with him? I instantly weighed the odds. It was a no-brainer, even though there wasn’t much of a sexual attraction.

Within what seemed like moments, we entered his fashion designer lair overflowing with a million different fabrics and thickly perfumed air. There was absolutely nothing wrong with Joe. Maybe a tad shorter than my usual tastes back then, but stocky, which I enjoy to this day. The problem with Joe was that he wore enough cologne to sink a ship and was as visibly gay as a $3 bill.

Today I genuinely appreciate, if not envy, a man confident enough to embrace his femininity. Yet, in those days, I was far less evolved and wasn’t ready to be automatically outed by virtue of some overly effeminate man with whom I happened to be seen. In other words, I was a fucking asshole.

Yet the truth of the matter, alcohol notwithstanding, is that I had made a calculated decision to fuck Joe that night because I wanted something from him. Not in the way that everyone wants something from someone — this was clearly a quid-pro-quo. He was no fool though. He knew how badly I wanted the Orion introduction, and he intuitively knew I would be willing to be strung along for as long as he dangled the prospect before me. Within reason.

For about a month, I had to service Joe. Formidably able to manifest boners on-demand – when all excuses had been exhausted — by pretending he was someone else. Increasingly I became physically repulsed by the scaturient taffeta and lace, and fucking for favors was becoming harder –- and softer –- to pull off.

The shame stuck to me with the pungency of his syrupy sweet cologne, no matter how often I showered. Eventually, I confronted him, and demanded he set up the meeting, despite the sinking feeling I was being played. Pathetically, whoring myself with fuck all to show for it.

But I was wrong. Joe did indeed know someone at Orion, and before I knew it, I was off to meet his friend who worked in Business Affairs for this prestigious Hollywood film studio.

I felt exhilarated making my way to Orion that morning. Orion was located in a beautiful, dark-tinted-glass building on Century Park East, right in the middle of Century City. Within spitting distance of Beverly Hills – although the surroundings seemed, perhaps, a little too corporate for a studio with a reputation for being one of Hollywood’s most artist-friendly, creative studios. But it was Orion fucking Pictures. Its iconic, italic logo proudly displayed above the entrance in white impressively contrasted against the building’s glossy, black façade. A logo I recognized from countless movies I had seen.

I had to pinch myself. I was excited by the enormity of a little nobody from Johannesburg potentially landing a job at this storied studio. And simultaneously anxious about how unqualified and inexperienced I was. Even though I vowed to myself, I was willing to do anything. Indeed, I already had.

Within a matter of a few months, I would become an Assistant to the President.

I was fourteen when I got to King David High School. It was such a relief to be at a school with girls again. So much easier for me to hide who I was with girls on my arms. Compared to the excess testosterone and lurking danger of Highlands North, King David was a breeze.

The disadvantage, however, was that King David had a higher standard of education than Highlands — being a private school and all — and so when it came to subjects like math, I was so far behind that it was impossible to catch or keep up. The problem with this is that children who feel left behind are treated with disdain by teachers who feel they are simply not applying themselves and are either stupid or disruptive—a self-fulfilling prophecy on their part, and one that I bought into and ran with.

The more teachers showered me with their disdain; the better it was for the rebellious image I was trying to cultivate. At Highlands North High, I had been too young, scared, and inexperienced to pull off this calculated image-making, but King David was the perfect institution to nail it. Once I added drugs to the mix, my street cred was as good as it got.

As my secret and intensely sexual relationship with Stuart continued unabated, I found myself increasingly attracted to the boys around me at school. Figuring out ways to mask what I knew I had become became imperative. I made a point of befriending the athletes and the jocks. The boys I found the most confident and attractive, which had their drawbacks. I was perpetually conflicted — a recurring theme for yours truly — over whether I wanted to fuck them or be them.

Unlike my well-honed — albeit imperfect — ability to hide who I was, Bryan Schimmel was less successful at it. And because he stuttered, it only made things worse for him. Children are inherently cruel, and the second they spot a perceived weakness, they prey on it, like sharks. Bryan was the perfect decoy to redirect any suspicion that might have been aimed at me. I didn’t just join in the bullying, though, I would also initiate it.

I remember punching him — physically inflicting pain — as a deflection, foolishly deluded into believing that my bullying made me more of a man, not less. So long as the focus was on Bryan, who was mercilessly mocked and branded with every anti-gay epithet under the sun, it wasn’t on me.

No one could possibly know how in love I was with Robbie Koseff, or how turned on I was by all the cool, popular boys I craftily and deliberately surrounded myself with if I was aggressively bullying Bryan. I vividly remember seeing the hurt and anguish on Bryan’s face. In his eyes. It’s ingrained.

If only I could rewind, I would have realized that the best way to assert my masculinity would have been as Bryan’s protector rather than his tormentor. To have demonstrated compassion rather than aggression and benefited from his brilliant, creative mind rather than cruelly capitalize on his fear and pain. But hindsight is always twenty-twenty.

Not surprisingly, our life paths would not be all that dissimilar. But I cannot — and dare not — take even an iota of credit for Bryan’s hard-fought, uncompromising resilience. Nor for the monumental musical talent he became — even if it was borne of the adversity he faced and the indignities and violence he suffered to get there. Nor for how he managed to magically cultivate and translate his pain into art. Having to deal with the bullying he endured, addiction, homophobia, and shame. His successful outcomes were by no means guaranteed. They were earned with literal blood, sweat, and grit.

Our paths never crossed after school, even though he also spent time in New York, and I only was reminded of him again a couple of years ago when it turned out we had a mutual friend from school with whom we were both still in contact. I had been quite surprised when he had accepted my friend request on Facebook, even though no conversations ever came of it, yet not all that surprised to notice how he had transformed himself into a hyper-masculine, muscled and well-toned, openly gay man.

I poured through his posts, impressed by all he had achieved as a musical director, pianist, lyricist, singer, and composer. A widely admired and celebrated musical prodigy.

I was again surprised when he agreed to meet for lunch.

Waiting for him at Tasha’s, a trendy Morningside eatery in Johannesburg, I felt anxious and trepidatious. Would he remember me for being the loutish, unkind bully I remembered being, or might he have seen something beyond that? Had he taken the time to explore my Facebook page to see whom I had become the way I had explored his, or was it arrogantly presumptuous to even think he might be interested? As people chatted around me, I wondered what I would say. How would I broach the topic?

When he arrived at the restaurant, I recognized him immediately. I walked over to greet him.

The first thing he said to me was: “I recognize you from your resting bitch face.” I grinned a little uneasily. Many a true word is spoken in jest, the saying goes, and although he smiled when he said it, I realized instantaneously that he remembered everything.

We ended up having an amazing conversation. Swapping stories about our lives, the various similarities and intersections, and the divergent paths we took. The bullying Bryan was forced to endure scarred him. Deeply. So significant and prevalent, he had given talks to schools — including our high school, King David — about the impact of bullying and how it affected his life. He had taken his bitter, soul-sucking experiences and parlayed them into a gift to prevent it from happening to other teens.

His honesty, vulnerability, and resolve humbled me, bringing tears to my eyes. I detested any role I had played in causing so much damage. For most of my life, my self-loathing for things I wasn’t responsible for caused me the most heartache. But this was one of the few exceptions where I was indeed the culprit and deserving of the derision I pored on myself. That I was capable of that callous cruelty remains cautionary for me, even though I no longer recognize that person. I remember him all too well.

Bryan got the opportunity to confront me on his terms. I got to hear it from his perspective, devastating as it was to listen to. I also got to apologize, a gift for which I am incredibly fortunate. Bryan didn’t owe me his forgiveness, and I had no right to expect it, and yet graciously and generously, he forgave.

We discussed the possibility of doing a talk together to demonstrate the awful cost and lost opportunities that arise from bullying and the power of reconciliation. A process that would require me to tap into and share one of the most shameful and ugly sides of me — and one I would just as soon forget ever existed. In some ways, this retelling is the beginning of that process. We both walked away from the lunch feeling freer and lighter.

I now get to appreciate Bryan for his talent and his resilience. And everything I missed out on and was deprived of by my violent behavior. He wrote about some of these themes for a one-man show he wrote, More Than a Handful. Astonishingly open and brave.

We have become friends. He’s my people. There is genuine love. He’s a member of my tribe and always will be. He always was; I just didn’t realize it. Although nothing can ever erase the harm I inflicted, I am incredibly grateful for his forgiveness and the opportunity even to try. Facing one’s shame is always hard work — in many ways, the essence of this book — but overcoming the shame I felt for how I treated Bryan Schimmel was among the most difficult and rewarding.

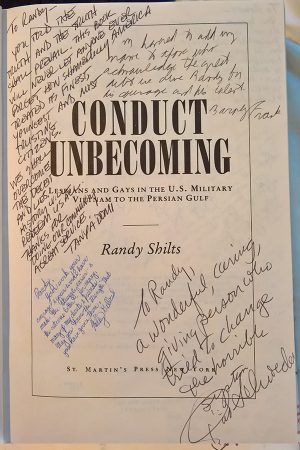

Clinton Fein asked some of those he interviewed to please write a note to Randy in his copy of the book if he had it with him. Some were written while Shilts was alive, and some were written posthumously. Fein decided to photograph and transcribe these notes for posterity. And more importantly, to depict the immense gratitude to Randy Shilts by those whose lives were so impacted by the cruelty of America’s policies towards gays in the military. And Fein’s gratitude to them.

These notes to Randy remind me of why we did what we did, the bravery of all those who fought back to eventually win, and the extent to which we are capable and must be willing to fight again. Our history is all too often whitewashed, or sanitized, or oversimplified for commercial consumption on streaming platforms.