Conduct Unbecoming Excerpts

Introduction

February 28, 1995 marked the first anniversary of the Armed Forces’ Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy on gays and lesbians in the military. Scrutiny of this policy’s implementation reveals a situation far worse than it was before. “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” continues to be a flagrant violation of the First Amendment, effectively silencing the ability to define one’s self. Just to say the words “I’m gay” is grounds for removal – not only from the military, but from a job, from future employment, and from a community of friends, sometimes family. To be allowed to exist in an environment where you are encouraged to be all that you can be – as long as you don’t tell anyone about it, and as long as you don’t act on your convictions – is psychological torture, and absurd government policy.

Conduct Unbecoming, a new CD-ROM from ApolloMedia based on Randy Shilts’ book about gays and lesbians in the military, highlights the inconsistencies inherent in this policy, and paints a picture that both disturbs and enlightens.

These excerpts are presented here serve as a vote for more enlightened government policy, and as a testament to the courage of gays and lesbians who have served, fought, and died for their country – and who suffered violent abuse under its leadership.

The Conduct Unbecoming Excerpts

The history of homosexuality in the United States armed forces has been a struggle between two intransigent facts – the persistent presence of gays within the military and the equally persistent hostility toward them. All the drama and controversy surrounding the demand for acceptance by lesbians and gay men in uniform represent the culmination of this conflict, one that dates back to the founding of the Republic.

Over the past twenty years, as the gay community has taken form in cities across the nation, a vast gay subculture has emerged within the military, in every branch of the service, among both officers and enlisted. Today, gay soldiers jump with the 101st Airborne, wear the Green Beret of the Special Forces, and perform top-level jobs in the “black world” of covert operations. Gay Air Force personnel have staffed missile silos in North Dakota, flown the nuclear-armed bombers of the Strategic Air Command, and navigated Air Force One. Gay sailors dive with the Navy SEALS, tend the nuclear reactors on submarines, and teach at the Naval War College. A gay admiral commanded the fleet assigned to one of the highest-profile military operations of the past generation. The homosexual presence on aircraft carriers is so pervasive that social life on the huge ships for the past 15 years has included gay newsletters and clandestine gay discos. Gay Marines guard the President in the White House honor guard and protect U.S. embassies around the world.

Never before have gay people served so extensively – and, in some cases, so openly – in the United States military. And rarely has the military moved so aggressively against homosexuality. The scope and sweep of gay dragnets in the past decade have been extraordinary. Their aim is to coerce service personnel into revealing names of other homosexuals. If investigators are successful, the probes turn into purges in which scores of people are drummed out within weeks. The pressure to cooperate is so fierce that lovers sometimes betray their partners and friends turn against one another.

The ruthlessness of the investigations and hearings serves a central purpose: to encourage lesbian and gay soldiers to resign from the military, to accept passively an administrative discharge or, if they are officers, to leave quietly under the vague rubric of “conduct unbecoming.” Such quiet separations help conceal the numbers of lesbians and gay men the military turns out of the service, as many as 2,000-a-year during the past decade.

In the past decade, the cost of investigations and the dollars spent replacing gay personnel easily amount to hundreds of millions. The human costs are incalculable. Careers are destroyed; lives are ruined. Under the pressure of a purge, and in the swell of rumors that often precedes one, despairing men and women sometimes commit suicide.

The military’s policies have had a sinister effect on the entire nation: Such policies make it known to everyone serving in the military that lesbians and gay men are dangerous to the well-being of other Americans; that they are undeserving of even the most basic civil rights. Such policies also create an ambience in which discrimination, harassment, and even violence against lesbians and gays is tolerated and, to some degree, encouraged. Especially for lesbians, the issues are far more complex than simple homophobia, because they also involve significant features of sex-based discrimination.

Of course, sex discrimination in the military’s enforcement of anti-homosexual regulations since 1981 mirrors deeper conflicts. We are a nation in transition when it comes to attitudes toward gender roles and sexuality in general, and homosexuality in particular. Military service was once considered a rite of male passage. This clearly was the case during the early years of the Vietnam conflict; and it remains so among those who were trained during that era of military history – the people who are at the top of the military’s chain of command today. In different ways, the presence of women and gays in the ranks challenges the traditional concept of manhood in the military, just as the emergence of women and gays in other fields has done in society at large.

In truth, homosexuals in this time and in this culture have very little control over many of the most crucial circumstances of their lives. Control resides with the heterosexual majority, which defines the limits of freedom for the homosexual minority. The story of homosexual America is therefore the story of heterosexual America.

– Randy Shilts, Excerpts from the prologue to Conduct Unbecoming

On August 30, 1975, Technical Sergeant] Leonard Matlovich in his crisp blue Air Force uniform was on the cover of Time magazine, over the bold headline I AM A HOMOSEXUAL. His picture could be seen at

every checkout stand and magazine rack in the country.

It marked the first time the young gay movement had ever made the cover of a major newsweekly. To a cause still struggling for legitimacy, the event was a major turning point. For the general public, the interest in Matlovich reflected a deeper, almost unconscious fascination with the incongruities of his case. On one hand, Matlovich defied everything people believed homosexuals were. The substance of his case, however, pitted the gay movement, the

ultimate affront to the ethos of American manhood, against the military, the last great bastion of male heterosexuality. At a time when sex roles were being called into question, the conflict was too archetypal for the media to resist.

For others in uniform, Matlovich’s message rang closer to home. One of these soldiers was Miriam Ben-Shalom, a 27-year-old single mother in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. For over a year, Ben-Shalom had spent every other weekend training with the Eighty-fourth Training Division of the Army Reserves. She was attending drill instructor’s school and would soon begin her stint as one of the first female DIs in the division. When she saw the Time cover, she asked her commander, “Why don’t they kick me out?” She was gay, too, and had been involved in lesbian-feminist groups for several years.

“Because you’re a good NCO,” the commander replied. He explained that the exercising of regulations was discretionary. This made sense to Miriam. As she continued her biweekly drilling, she formed a resolution that one day people should know they allowed open lesbians in the Army.

About the time that Jay Hatheway was court-martialed and Copy Berg faced his separation hearing, Sergeant Miriam Ben-Shalom graduated from drill sergeant’s school in Milwaukee. Not only was it a very proud moment in her military career but it was also the time she had chosen for her “coming out,” as the public acknowledgment of being gay was now called in activist circles. It was a time she had been moving toward since her conversation with her commander at the height of the publicity surrounding Leonard Matlovich. Later, her commander asked her again whether she was a homosexual.

“Sir,” Shalom answered, “homosexual is an adjective.”

“You know what I mean,” he said impatiently.

Yes, she said, she was.

Now she had decided to let other people know about it, too, and she told reporters for the local gay newspaper that she would be graduating that night.

“How does it feel to be a lesbian in the Army?” a reporter asked her.

“It feels like everybody else,” she answered.

Though her commander had been willing to accept a privately lesbian sergeant, he was not ready to retain a publicly gay one. A few days later, furious, he confronted her. “Why didn’t you say, ‘no comment’?” he asked. With that, he initiated discharge proceedings. Miriam Ben-Shalom knew that her performance evaluations documented that she was as good as any soldier in the Army Reserves, and a good deal better than most. She decided to fight such proceedings – all the way to the Supreme Court if she had to.

With that decision of the then-unknown substitute teacher in Milwaukee, the stage was set for the next 15 years of legal maneuvering around the issue of homosexuals in the military. Until well into the 1990s, when people talked about the civil rights of gays in uniform, or, for that matter, the civil rights of gays in the United States, the names of those whose court cases would be most frequently cited were Matlovich and Berg, Ben-Shalom and Jim Woodward, Jay Hatheway and, within a few years, Perry Watkins. As these people began the arduous process of seeking redress through the federal court system, their names were reduced to the italics on the covers of legal briefs: Matlovich v. Secretary of the Air Force, Ben-Shalom v. Secretary of the Army, and so on. As they left the military, they would help define the legal limits of freedom for homosexuals in the United States.

Copyright 1995 ApolloMedia ™ Corporation. All rights reserved.

Copyright 1993 Randy Shilts. Copyright 1994 Estate of Randy Shilts. All rights reserved.

Published by arrangement with St. Martin’s Press.

And they were extraordinarily close, to the point that Copy knew what his father was thinking just by looking at him, as if they were the same person. They did virtually everything together until the commander went to Vietnam in 1967 to minister to the Marines.

Copy began establishing his own track record of being a winner then. He was not just another track letterman at Frank W. Cox High School; he was also student-body president. At Boy’s State, he was not just a delegate, he was a candidate for governor. At Boy Scout Troop 422, he was not simply another Life Scout, he was AlowatSikima, Chief of Fire, the top position of the elite Order of the Arrow fraternity for the entire Chesapeake Bay area. Whenever local chapters of the Lion’s or Rotary or Optimist’s Clubs needed a good teenager to speak, they trotted out Copy Berg.

With its lackluster architecture and landscaping, Norfolk Naval Station had the nondenominational look of all military installations. Inside the gate, past the navy blue jet fighter that seemed to fly out of the ground on iron legs, were signs of a moment of glory that had touched the site once, when an exposition there had featured pavilions from every state in the nation. A two-third-scale reproduction of Independence Hall still stands from that time, not far from the stately row of admirals’ homes. Other than this Colonial touch, there was little about the place that spoke of its role as the capital of the United States Navy.

On an unseasonably cold and windy January morning in 1976, however, it was clear by the number of reporters descending on the place that something important was happening. Uniformed guards politely directed members of the media to a two-story red brick building, one of three identical buildings surrounding a dusty courtyard. Inside, under the fluorescent lights of a hearing room, an administrative board took up the case of Ensign Vernon E. Berg III, the first officer in the history of the Navy to say he was a homosexual and wanted to stay in the military.

While the attorneys dug into their law books, Copy worried about whether his father would make the trip to Norfolk when the separation hearing began. His lawyers were unanimously opposed to having the senior Berg appear. No one was sure what he would say. He could hurt Berg’s case if he came down on the side of the antigay regulation.

Copy did not think his father would hurt his case. On one level, he appreciated the significance of walking into the hearing alongside his father, a career Navy man like those who would be judging him. This, however, was an almost trivial consideration in comparison with the main issue. He could stand losing his bond with the service, but he could not stand losing his father. It would be like losing a part of himself.

As the date of the hearing neared, he awaited word from Chicago; finally it came. When did the hearing start? Commander Vernon Berg asked Ensign Vernon Berg when he finally called. He wanted to be there.

The climax of the eight-day hearing occurred the next morning when a sandy-haired Navy commander took the stand. His dress blue uniform only highlighted the striking resemblance the man bore to the defendant. On his chest, among all the other ribbons Commander Vernon Berg, Jr., had accumulated during the course of his career, was the Bronze Star he had won when he almost died ministering to Marines during the Tet offensive. In the middle of the red, white, and blue ribbon was the letter V – for valor. Berg’s Navy lawyer, Lieutenant John Montgomery, asked the chaplain about his experiences with gay sailors.

“A person is a person,” Berg began. “I really have felt strained in this whole hearing about people saying homosexuals have different problems. They have the same problems as anybody else. A homosexual can perform badly or spectacularly well. Homosexuals that I have known in the military have done extremely well, getting to extremely high ranks after I first met them.”

“Are you saying that you know of homosexuals who are officers in the United States Navy today?” Montgomery asked.

“Certainly,” the chaplain answered.

“Do you know any of them of the rank of commander?”

“Certainly.”

“The rank of captain?” Montgomery asked.

“Certainly.”

“The rank of rear admiral?”

“Yes, sir,” Berg said. The room fell utterly silent while the chaplain continued. “Therefore, I would like to interject that I think it behooves all of us to look at what we do. We condemn blindly with prejudice and, you know, we must be careful whom we condemn.”

When Montgomery asked about Berg’s experience as a chaplain to Marine units in Vietnam, the commander said that at least once a week one or another Marine would come to him and admit to being gay. He also acknowledged, somewhat painfully, what he would have done not too long before if a commander had sent him a gay soldier.

“This week has been a learning experience for me,” the elder Berg said, “and I’m sure it has been for all of us. I’m a product of Navy society also, and, sadly to say, years ago in 1960, ’61, ’62, I would have told him carte blanche, ‘If you are a homosexual, you had better get out’.”

The world was changing, he added, looking toward his son. “We are advancing into an age of enlightenment. Hopefully, that will make such inquisitions unnecessary in the future.”

The elder Berg walked down the aisle of the hearing room as Lieutenant Artis began reading from the Navy’s regulations on homosexuals again: “Under ‘Policy,’ paragraph four, it’s very clear, very insistent, the way I read it….”

The voice faded into background noise as Copy watched his father walk from the stand. Commander Berg had rarely discussed his Vietnam experiences, and now Copy could see why. A part of the chaplain still grieved for the dying Marines he had held in his arms. Copy had never seen his dad so emotional; he had never seen him so mortal; he had never loved him more.

When Copy focused again on the proceeding, he was consumed with resentment that the officers could so roundly ignore what his father had just said and so easily slip back into quoting SECNAV instructions. There were many things that would long anger Copy Berg about the hearing, but nothing more than a board that asked a man to resurrect the most painful moments of his life and then answered him with quotes from a rule book.

There was a second painful understanding Copy came to that day. He had learned for the first time what his father thought of homosexuals there, in a hearing room in answer to a lawyer’s questions, because he had not had the courage to ask such questions himself.

Copyright 1995 ApolloMedia ™ Corporation. All rights reserved.

Copyright 1993 Randy Shilts. Copyright 1994 Estate of Randy Shilts. All rights reserved.

Published by arrangement with St. Martin’s Press.

Select Media Reviews

Conduct Unbecoming, a CD-ROM based on his 1993 homonymous book on gays in the military, gives us a tantalizing peek at the potential of CD-ROM publishing. Here a good book is rendered even more readable and accessible…….The CD-ROM version takes Shilts’s work to a new level of accessibility and comprehension.

Jon Katz, WIRED Magazine

Rather than pretending to be mere data, this disc is purposefully a political statement and is, therefore, an evolutionary CD-ROM.

Stewart Wolpin, Rolling Stone

The military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy on gay servicemembers took on a whole new meaning after a S.F. multimedia company started putting together a CD-ROM on the subject.

John Gilles, Marin Independent Journal

The new CD-ROM version of Randy Shilts’ massive history of gay men and lesbians in the U.S. military is full of tantalizing surprises ….. on the CD version, there is something about actually seeing the grace and honesty of a person fighting through tears to tell the truth that has no comparison in print.

Pat Holt, San Francisco Chronicle

Conduct Unbecoming, a new CD-ROM from ApolloMedia based on Randy Shilts’ book on gays and lesbians in the US Military highlights the inconsistencies inherent in this policy and paints a picture that both disturbs and enlightens.

HotWired

The military hates to have any lights shown on what it is doing. This CD-ROM is like flicking on the lights in the kitchen.

Kate Dyer, former legislative assistant to Congressman Gerry Studds

The well-intended product expands the printed book to include audio interviews, photographs,resource materials and helpful nudges toward letter-writing activism. The political consciousness is highly commendable, not to mention extremely rare in the interactive market…

Glen Helfand, New Media Magazine

Not only is Conduct Unbecoming entertaining and thought provoking, but it is also a tool for changing this hateful policy which needs to be changed.

U.S. Representative, Congresswoman Lynn Woolsey

The young, San Francisco-based ApolloMedia Corporation has produced an electronic version of this historical investigation of gays and lesbians in the U.S. military that expands the print to include brief oral histories, photos, hypertext links, and extensive resource guides and bibliography.

San Francisco Review of Books

A small multimedia publisher has gone head to head against the US Navy and came out on top. San Francisco based ApolloMedia forced the Navy to hoist the white flag in a month long battle to include a recruitment poster in the CD-ROM version of Conduct Unbecoming…

Farhan Memon, The New York Post

A Navy lawyer told ApolloMedia, which produced of the CD-ROM, that if it used a 1972 recruitment poster in Conduct Unbecoming, it would be “in big jeopardy.”

The Navy claimed that the US Naval Academy crest was a registered trademark. The poster features Ed Graves, an Annapolis graduate and the Navy’s first black poster boy. The Navy stopped using the poster after learning that Graves is gay.

Refusing to bend, ApolloMedia informed the Navy of its intent to use the image anyway, and for a moment, it looked as if neither side would blink. But after mulling over the looming publicity nightmare (ApolloMedia called a press conference to announce the Navy’s actions), and forcing the Navy into an unwinnable First Amendment battle, the Navy eventually withdrew its threats in a humiliating defeat.

The CD-ROM version of “Conduct Unbecoming,” based on Randy Shilts’s masterpiece of a book by the same name, provided a comprehensive and visually impactful portrayal of the struggles faced by gay men and lesbians in the US military.

The inclusion of filmed segments featuring servicemembers, key litigators and politicians added a powerful emotional element to the narrative.

The e-Post feature represented the first time a user could use tech to contact senators and congress members. Rolling Stone magazine called the CD-ROM evolutionary.

Overall, the groundbreaking CD-ROM used images and video to effectively humanize lesbian and gay servicemembers.

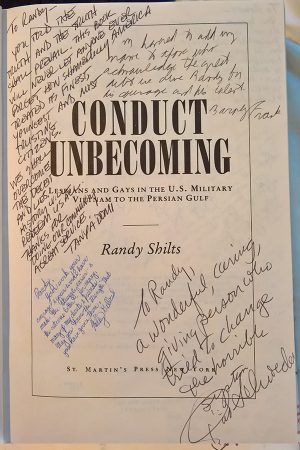

Clinton Fein asked some of those he interviewed to please write a note to Randy in his copy of the book if he had it with him. Some were written while Shilts was alive, and some were written posthumously. Fein decided to photograph and transcribe these notes for posterity. And more importantly, to depict the immense gratitude to Randy Shilts by those whose lives were so impacted by the cruelty of America’s policies towards gays in the military. And Fein’s gratitude to them.

These notes to Randy remind me of why we did what we did, the bravery of all those who fought back to eventually win, and the extent to which we are capable and must be willing to fight again. Our history is all too often whitewashed, or sanitized, or oversimplified for commercial consumption on streaming platforms.