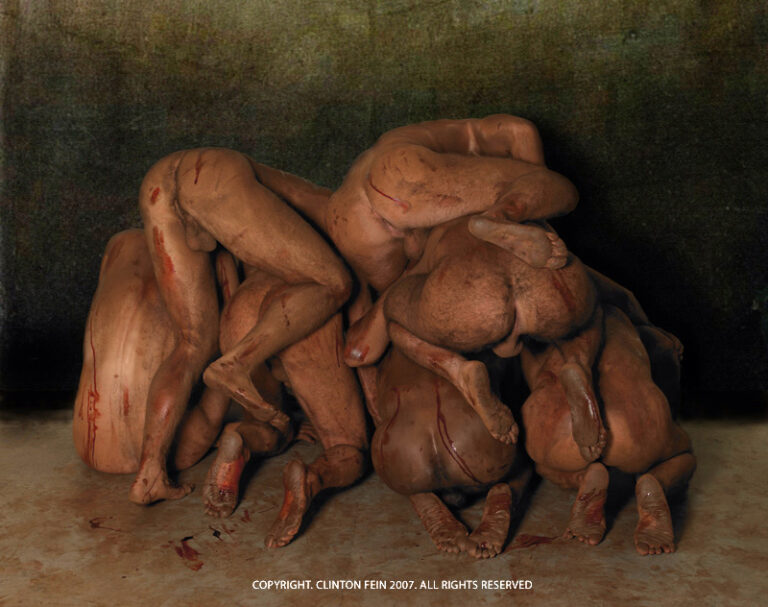

A very different reckoning of photography’s role in delivering the truth is offered by Clinton Fein, who repurposed photographic appropriation to make a series of works based on the pictures of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib that came to public attention in April 2004. A South African-born, San Francisco-based First Amendment activist, Fein hired models to reenact the notorious compositions (detainees piled in a human pyramid, forced to simulate fellatio, handcuffed to beds and bars in extreme positions), illuminated the tableaux vivants with penumbral and strangely intimate lighting, and displayed the enlarged pictures as high-quality chromogenic prints mounted on panel. (The originals and the reenactments can be com- pared at www.clintonfein.com.)

Fein’s counterfeits are not intended to reprise tired debates about originality and authorship. Unlike Sherrie Levine, who rephotographed Walker Evans’s Depression-era images, or Thomas Ruff, whose enlargements of Internet images preserve and accentuate the flaws of screen grabs, Fein seized upon despicable amateur images, which unexpectedly had acquired public notoriety and probative value, and re-presented them in enhanced, painterly terms. His invocation of old- master painting, far from summoning up Christian martyrdom as do the Abu Ghraib canvases of Fernando Botero, delivers us to the dark threshold of inhumanity conjured by Goya.

A free speech watchdog, Fein also observed that when the soldiers’ snapshots were picked up on the Web and disseminated by establishment news sources, online and in print, the genitals of the nude prisoners were blurred (as genitals are when the news media reproduce garden-variety pornographic images). That concession to good taste, Fein contends, served to downplay the sexual sadism and degradation inherent in the forms of abuse devised for the occasion, qualities he sought to restore to the situations when he pictured them. He further notes that the original Abu Ghraib pictures were themselves staged, with body pyramids topped off and thumbs-up signs flashed with an awareness the camera’s presence and appetite. Curious about the moral proximity between witnessing and instigating, Fein set out to see if he might understand (he says that he did) something of the “mindset” of the abuser by assuming the role of photographer in the reenactment. In the end, and once again in contrast with Botero’s canvases, Fein’s photographs are about the torturers – the photographers among us – and not the victims.

It was 1968. On February 2 the New York Times printed a photograph by Eddie Adams on its front page, four columns wide. The image showed General Loan, a South Vietnamese general, executing a Vietcong suspect in civilian clothes. It was strikingly beautiful, the background in soft focus, the foreground displaying Loan’s flexed forearm and his devil-horn tufts of hair. Americans were also struck by its simplicity: this was war boiled down to two men and an execution, no complex maneuvers or military jargon. Harry McPherson, a speech-writer for President Johnson, saw the image and observed: “You got a sense of the awfulness, the endlessness, of the war and, though it sounds naive, the unethical quality of a war in which a prisoner is shot at point-blank range. I put aside the confidential cables. I was more persuaded by the tube and by the newspapers. I was fed up with the optimism that seemed to flow without stopping from Saigon.” This photograph, a frozen moment, seemed to stop the endless flow. And its impact was remarkable: after the image was reprinted across the world, public opinion polls showed the greatest single shift ever recorded by Gallup. Between February and March, doves jumped from 25 to 40 per cent, and hawks dwindled from 60 to 40 per cent.

Fast-forward four years, to 1972. Nick Ut’s image of Kim Phuc fleeing her village after an accidental napalm bombing appeared in every American newspaper on June 9, a day after Ut shot the image. Like Adams’ image, Ut’s was beautiful, with a full contrast of blacks and whites and a soft focus smoky backdrop. It had elements of Greek tragedy: the face of the young boy on the left of the image is shaped like the mask of Greek tragic drama. And it resonated with familiar Christian iconography as well, for Phuc is stretched out as though crucified.

The image didn’t stop American pilots dropping napalm on Iraqi troops during the 2003 advance on Baghdad. But it did shift public opinion on the Vietnam War.

Fast-forward again, to 2004. In April, 60 Minutes II released digital photographs taken by U.S. prison guards at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. The images were printed on April 30 by the New Yorker. But this time the images quickly faded from the national scene. Unlike the Vietnam images, they were easily swept aside. This difference in impact wasn’t due to a difference in intent: Eddie Adams regretted destroying Loan’s reputation with his 1968 photograph, explaining in an interview that the image was never meant to do what it did. Adams’ image just took on a life of its own within the antiwar movement, beyond the photographer’s intention. The Abu Ghraib images, however, failed to find that new life and be taken up as protest material. Squinting at the images in newspapers and online, it was hard not to wonder if this low impact was partly due to their low quality; they were perhaps too grainy, too badly lit, too drained of color, too flattened, too muted. A far cry from the great images of the Vietnam war, these images were simply forgettable.

One last fast-forward, this time to 2007. In January Clinton Fein offered his own versions of the Abu Ghraib images: large-scale, hyper-detailed, dramatically-lit and uncensored recreations of the torture scenes that rival the visual explosions of the Vietnam War. There are, of course, numerous ways to respond to Fein’s exhibition. The viewer could feel like it revictimizes the prisoners within a pornography of violence, or that it forces a painful identification with the guards (those white faces staring back like a mirror-image for visitors), or that it offers a mourning ritual and a rummaging through the dark drawers of history’s closet-a history that America forgot so quickly in 2004. Perhaps the exhibition does all these things. But it is also an act of patriotic dissent. After all, as Fein once said to me: “dissent is the most powerful tool America has, and ensuring its protection is the most patriotic thing an American can do.” And in re-photographing the Abu Ghraib images, Fein entered a tradition of dissent that extends way beyond the Vietnam images-a tradition that, from Tom Paine to Tupac, has asked America to be America.

Like Fein and the Vietnam photographers, artists within the protest tradition have combined aesthetics and ideologies. Offering a poetics of engagement, the protest tradition has made form central to political protest. “For me this is better propaganda than it would be if it were not aesthetically enjoyable,” said Glenway Wescott of Walker Evans’ photographs in 1938, going on to further explain the importance of form to protest-“It is because I enjoy looking that I go on looking until the pity and the shame are impressed upon me, unforgettably.” Looking at Fein’s photographs, this is exactly what comes to mind: I enjoy looking and so I go on looking until the pity and the shame are impressed upon me, unforgettably.

Fein is even more deeply rooted with in the protest tradition through his use of appropriation. Audre Lorde once declared that “the master’s tools can never dismantle the master’s house.” But there is a long tradition of doing exactly that: for centuries, American artists have appropriated images, ideas, and language for their protest. The abolitionists used technical diagrams of slave ships to protest slavery. James Allen recontextualized photographs that were originally taken to celebrate lynchings for his exhibition Without Sanctuary (2000). Anti-lynching protest writers stole the rhetoric and imagery of Christianity from lynch mobs: creating figures of black Christs, writers like W.E.B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes met white supremacists in their own performance space. And Ida B. Wells fashioned her anti-lynching protest pamphlets from material generated by lynchers themselves: she quoted white newspapers at length, explaining that “out of their own mouths shall the murderers be condemned.”

Transforming the Abu Ghraib images for his own shockingly beautiful purposes, Fein makes his art a similarly appropriate process.

Another aspect of Fein’s art that roots him in the protest tradition is his use of shock value. For example, Abel Meeropol, who wrote the lyrics for Billie Holiday’s lynching anthem “Strange Fruit” (1939), once observed that Holiday’s voice could “jolt the audience out of its complacency anywhere.” Equally, the poet John Balaban explained in a recent interview that his early poems about Vietnam were meant to “shock and sicken” his American audience, and the novelist Tim O’Brien notes that the shock-value in his work “awakens the reader, and shatters the abstract language of war.” O’Brien adds: “So many images of war don’t endure for the reader-it’s the effect of a TV clip followed by a Cheerios ad. But my fiction asks readers not to shirk or look away.” And John Steinbeck once claimed to have done his “damndest to rip a reader’s nerves to rags,” with The Grapes of Wrath (1939). The breast-feeding tableau in Steinbeck’s novel is intended to shock, as are the meat-packing scenes in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906), James Agee’s descriptions of masturbation in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), and the suicide scene in Rebecca Harding Davis’s novella Life in the Iron Mills (1861). Critiquing our culture of fear, and the Bush administration’s “Shock and Awe” military policy, Fein’s art is similarly calculated to shock-to inspire outrage, agitation, and a desire to reach for change.

Beyond his politics of form, use of appropriated material, and employment of shock value, Fein is located within the protest tradition still further. His exhibition uses the device of the embedded artist to suggest artistic empathy. Fein appears in the exhibition himself as a prison guard, looming from the walls just Walker Evans’ shadow loomed over dustbowl migrants from behind the camera in 1930s Alabama. The decision to include himself within “Torture” summons a vision of the empathetically engaged artist, reminding us that protest artists have often worked with empathy as well as shock value-have suggested sharing another’s suffering in order to help end it. Some imagined themselves as their subjects, often painfully so: the early twentieth-century photographer Lewis Hine said he needed “spiritual antiseptic” to survive, and Upton Sinclair described the “tears and anguish” that went into his novel The Jungle. Others asked the reader to become the subject: James Agee noted that he wrote repetitiously because he wanted the reader of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men to experience for themselves the boredom of tenant farmers’ work.

Yet Fein’s work goes beyond this empathetic engagement. He features as a prison guard in this exhibition, and so emphasizes the dark side of engaged art-a troubling relationship between artist and subject. This dark side lurks throughout the protest tradition. For example, when Eddie Adams photographed General Loan in 1968, Loan treated the execution as a performance. He led the prisoner towards journalists, as though, without these witnesses present, he might not have bothered to pull the trigger. Watching and witnessing here provoked and defined an execution, and this complicated the morality of looking. Equally sinister is the fact that lynchings were a lucrative business for photographers, who would regularly document them. Some were even delayed until a photographer arrived, and mob, audience, and police officials regularly posed with the corpses. Many images were sent as postcards through the mail to participants’ friends and relatives, often with the sender’s face marked and a note to the effect of: “This is the barbeque we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe.”

Like Loan’s execution and America’s lynchings, the acts recorded in the original Abu Ghraib images look like performances for the camera’s eye, as though the greatest shame of all was to have the moment documented for an audience, for posterity. And by including himself within the exhibition, Fein engages head-on this question of the photographer’s presence at scenes of violence. Perhaps the artist is as sinister a figure as the original prison guard. Perhaps Fein enjoyed making violence as beautiful as this, and now asks us to enjoy it-asks us to take as much pleasure in these scenes as the original prison guards, with their grins and gestures. Perhaps Fein’s camera, which demanded of his models full nudity and physical exhaustion, is as aggressive as the prison guard’s club.

Making his camera a weapon of torture, Fein again echoes a tradition in the protest tradition: that of imagining words as weapons, pens as swords, cameras as guns. Richard Wright imagined “using words as a weapon, using them as one would use a club.” Amiri Baraka depicted words as daggers, fists, and poison gas in his poem “Black Art” (1966). James Agee called the camera a gun, Jacob Riis said he photographed the poor like a “war correspondent,” and for years Woody Guthrie had a sign on his guitar that read, “This Machine Kills Fascists.” In 1970, the Black Panther Party member Emory Douglas told artists to “take up their paints and brushes in one hand and their gun in the other,” adding: “all of the Fascist American empire must be blown up in our pictures.” Part of this tradition, Fein’s appropriation of the master’s tools transforms those tools into weapons that violently dismantle the master’s house, shock us into questioning the role of the photographer as a witness, and ask us to question our own role as new witnesses to these scenes.

One final aspect of Fein’s exhibition that locates him with the protest tradition is his strategy, quite simply, of remembering. In 2007 he remembers the early part of the Iraq War by re-photographing its images. It is an act reminiscent of the late twentieth-century photographers who found and re-photographed Walker Evans’ Alabama sharecroppers from the 1930s, and it is in the tradition of all protest artists who revise protest texts and images from an earlier time. To cite just one example, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) was used as a model by Edward Bellamy and Upton Sinclair, as a negative spur by James Baldwin and Carl Wittman, and was eventually transformed by Bill T. Jones in a 1990s ballet. It is as though Stowe’s novel needed corrective dialogue with other protest artists to make it whole.

In re-photographing Abu Ghraib, then, Fein enters a long tradition of intellectual bricolage. He salvages pieces of America’s past, and makes them new and whole. It is as though he takes the rubble of history and builds a theater space for a new performance-becoming a new Angel of History. As Tony Kushner observed in a recent interview, alluding to Walter Benjamin’s famous “Angel of History”: “you have to be constantly looking back at the rubble of history. The most dangerous thing is to become set upon some notion of the future that isn’t rooted in the bleakest, most terrifying idea of what’s piled up behind you.” Fein stares directly into the rubble, sees what is piled up behind us, decides that art can be made from what America has left, and invites a move from cultural haunting to social action-as though looking back might move America forward.

Zoe Trodd is a member of the Tutorial Board in History and Literature. Harvard University.

Clinton Fein currently exhibits horrifying high-resolution C-prints depicting (through carefully staged reenactments) the torture of prisoners by the American military at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. For some time Fein’s political images have been immersed in controversy and dissent. A native of South Africa, he left that country, with its harsh climate of censorship during apartheid, for the U.S., hoping to find truly free expression. Becoming aware of deep flaws in the application of the First Amendment of the Constitution, he filed suit against Attorney General Janet Reno in 1997, seeking declarative and injunctive relief from the provisions of the Communications Decency Act. The suit made its way to the Supreme Court, and Fein won the case. He insists on the fundamental right to annoy and created a Web site in pursuit of that end, maintaining that indecency is one of the most effective tools to counter public apathy.

Clinton Fein currently exhibits horrifying high-resolution C-prints depicting (through carefully staged reenactments) the torture of prisoners by the American military at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. For some time Fein’s political images have been immersed in controversy and dissent. A native of South Africa, he left that country, with its harsh climate of censorship during apartheid, for the U.S., hoping to find truly free expression. Becoming aware of deep flaws in the application of the First Amendment of the Constitution, he filed suit against Attorney General Janet Reno in 1997, seeking declarative and injunctive relief from the provisions of the Communications Decency Act. The suit made its way to the Supreme Court, and Fein won the case. He insists on the fundamental right to annoy and created a Web site in pursuit of that end, maintaining that indecency is one of the most effective tools to counter public apathy.

In a 2004 exhibition at Toomey Tourell he exhibited a striking image, Who Would Jesus Torture?, depicting George W. Bush on the Cross, an American flag wrapped around a phallic missile emerging from his loincloth. Derisive images, also digitally manipulated, of Rumsfeld, Cheney, Wolfowitz and company, as well as of Pfc. Lynndie England, poster girl for the Abu Ghraib outrages, are also included in this picture. The printing company Fein had hired to produce the digital image ultimately refused to release it and threatened to sue the artist for defamation. In the end, Fein managed to come up with an alternate printer willing to produce the image in time for his exhibition.

The recent show, titled “Torture,” consisted of staged and manipulated photographic images. Fein felt that the low resolution of the pictures taken by the GIs participating in the Abu Ghraib abuses – the images that later appeared in the press – had the effect of muting and veiling the actual horror of the scenes depicted. Only sharp, high-resolution images, he concluded, could convey the full impact of the humiliating atrocities and show what the corrupt leaders of a supposedly civilized nation routinely endorsed.

The Columbian artist Fernando Botero was so deeply shocked by the spectacle of Abu Ghraib that, instead of his ebullient images, he produced a suite of over 100 provocative paintings and drawings [see A.i.A., Jan. ’07]. Other artists — Richard Serra, Gerald Laing, Jenny Holzer and Paul McCarthy among them – have taken the disgrace of Abu Ghraib as subject matter for their art. But it was Fein’s notion that a full reenactment of the terrifying poses into which prisoners were forced was in order. After all, the original photographs were themselves staged, intended as trophy images, much like those by-now familiar photographs of lynchings in the American South, images crowded with the smiling faces of all who had come to see. So Fein re-created, for instance, the picture of Pfc. England holding a naked prisoner by a leash while pointing to his genitals. Another re-created photo shows a naked detainee made to masturbate another prisoner. Sadomasochistic sexuality, which is implied in the original snapshots, is stressed in Fein’s prints. The artist is well aware of America’s fascination with sex and violence, attested to by much of the current fare in movies and TV.

The hooded prisoner with the electric wires tied to his hands has become the unofficial logo of the present war in Iraq. For the 2004 election, Serra made a poster of this image, and it has also been restaged by Fein. So has the picture of the human pyramid of naked men, an image to which the artist has given the title Rank and Defile (2007). In addition to the photographs that simulated the original snapshots, there were also two entirely fictional C-prints in the show. Crucifiction 1 and 2 (2007), for example, are the artist’s imagined views of what it is like to collapse under extreme physical abuse.

Torture of detainees or their rendition to countries with even more abusive torture regimens has become semi-legal under the Bush administration. Fein reminds us, however, that these practices can never be anything less than intolerable. Otherwise, the real war is already lost.

By Peter Selz

Art in America

Fein’s ‘Torture’ at Toomey-Tourell: Anyone prepared to experience whiplash from changes in the terms of art over the past half century should go directly from Hackett-Friedman’s show to Toomey-Tourell, where South African-born Clinton Fein presents “Torture.”

Fein’s ‘Torture’ at Toomey-Tourell: Anyone prepared to experience whiplash from changes in the terms of art over the past half century should go directly from Hackett-Friedman’s show to Toomey-Tourell, where South African-born Clinton Fein presents “Torture.”

Several contemporary artists have tried to evoke the grotesqueries of war: Leon Golub (1922-2004), in his imaginary portraits of mercenaries, and more recently Fernando Botero, in a series of paintings and drawings reinterpreting the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib, near Baghdad. Some of the Boteros will come to UC Berkeley later this month.

But no one else has reached the peculiar extremes to which Fein goes. Using hired models, he re-enacted and photographed scenes of cruelty that were recorded in the notorious unofficial photographs of “detainee abuse” at Abu Ghraib. Fein presents these images as giant panel-mounted chromogenic prints.

To viewers who remember the Abu Ghraib images, Fein’s pieces will look both grimly familiar and oddly aestheticized. Two are his inventions.

Encountering them in an art gallery provokes tangled responses: outrage that someone would advance his own ambitions through the degradations the Abu Ghraib photos record; perverse temptation by the opportunity to study the mise-en-scene of the original pictures, safe in the knowledge of seeing simulations; despair that history has again diverted the resources of art away from pleasure and contemplation to bleak and urgent critical functions; and, finally, the recognition that, after all the barriers between art and life come down, nothing insulates our enjoyment of the arts against toxic pollution from our knowledge of real events.

How far should simulation in art go? Will we next have to ponder a re-enactment of, say, Saddam Hussein’s execution, or even Daniel Pearl’s, merely because these images can be found on the Internet, and because they symbolize the degeneration of American foreign policy?

Do Fein’s provocations really differ in spirit from the policy wonks who contrived punitive sanctions on the Iraqi populace for failure to unseat their ruler? Is the tepid American public reaction to official torture and lawlessness a sign of moral weakness? Of learned helplessness? Of both?

The absence of text in Fein’s new work — he often relies on it heavily — leaves space in a viewer’s mind for recall of the administration’s weasel words misnaming and justifying torture.

By bringing into the art setting simulated images of some of the Abu Ghraib horrors, Fein forces thoughtful viewers to reflect on our — American culture’s — proven taste for simulated violence. Prosperous First World citizens seldom confront real violence, but we welcome depictions of violence with alarming frequency and enthusiasm.

How long can we go on — collectively and individually — exciting ourselves with pictured violence before only the excitement matters to us? Can we call this pattern anything but pornographic?

Fein’s work, despite its debatable standing as art, or maybe because of it, takes us to this level of reflection, whether we want to go there or not.

The Horror of Torture, Reinterpreted through Art

By Kenneth Baker

Kenneth Baker has been art critic for the San Francisco Chronicle since 1985. A native of the Boston area, he served as art critic for the Boston Phoenix between 1972 and 1985.

He has contributed on a freelance basis to art magazines internationally and was a contributing editor of Artforum from 1985 through 1992. He continues to review fiction and nonfiction books for The Chronicle, in addition to reporting on all aspects of the visual arts regionally and, on occasion, nationally and internationally.

When first reports emerged about the Abu Ghraib abuses, as well as graphic pictures of American military personnel in the act of torturing the prisoners, the world fell under the spell of instant shock, disgust and horror.

Even more shocking was the discovery that these acts were committed by personnel of the 372nd Military Police Company, CIA officers, and contractors involved in the war and occupation of Iraq.

The shots depict both victims and torturers posing for the camera. There’s a naked man kneeling in front of another man as if performing oral sex. A naked man on a leash held by a female American soldier. Naked men in chains. Naked men stacked up in a pile, and others include forced masturbation. Whether the sexual acts were performed or simulated, the prisoners were forced to perform as pornographic “actors.” The resulting political scandal damaged the credibility and public image of the United States and its allies in the prosecution of ongoing military operations in war-torn Iraq.

As they first appeared on the Internet, the torture images of Iraqi prisoners were crude, many unmistakably pornographic in intent, and easily dismissed because of their poor quality. The spectacle of Abu Ghraib revealed disturbing truths about American politics, sexuality and morality.

In contrast, Clinton Fein’s staged and digitally manipulated photographic images of the Torture series are deliberate, choreographed to bring back to the center of public discourse the shameful events of Abu Ghraib. The added high resolution of the photos elevates the experience to an artistic high and brings many issues into a sharp focus. Through Torture, Fein memorializes the Bush legacy of a Post 9/11 world so openly and shamelessly practiced.

The South African Bay Area resident is an accomplished artist and a recognized persona that has become a dot.com phenomenon of the virtual space and a voice to reckon with on the cultural landscape. After 10 years of prolific output (Annoy.com), Fein is synonymous with controversial art and digging deep into what the average American citizen or the mainstream would like to forget, ignore, deny or simply bypass. In undertaking the Torture series, Fein has once become our conscience, a moral agent.

Torture is not the brainchild of Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld. Sadly, it has a long history that has been exhaustively documented in best-seller books, declassified documents, CIA training manuals, court records, and special commission reports. The embrace of torture by US officials long predates the Bush Administration and has, in fact, been integral to US foreign policy since the Vietnam War.

As a commentator of the Bush Administration’s doing and undoing (Numb & Number 2004), Fein has taken the matter into his hands and commits the despicable acts of torture on 9 panels of C-Type chromogenic prints.

Fein doesn’t simply restage the happenings of Abu Ghraib’s correctional facility; he picks the news bytes by reproducing the scenes and disturbs our reality and complacency. A series of staged and digitally manipulated photographic images recreate the infamous torture scenes from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, transforming the diffuse, muted, and low-resolution images into large-scale, vivid, powerful, and frightening reproductions.

In Torture, Fein takes us beyond his trademark graphic editorialization and Photoshop montages to digitized, staged and human-scale photographic panels to confront the ugly reality the Bush administration does not want us to see, and to which the mainstream pays so little attention. Where mainstream media leaves off, Fein unabashedly recreates a visceral experience of profound effect. He forces us to look, reexamine and question the ugliness of war and the government’s highest-ranking officials who are complicit in these atrocious acts.

The Torture series, in its entirety, is best appreciated when considering the artist’s intent. Present-day reality is layered with a rich history as far-reaching as the Civil War. Fein’s Torture must be viewed in a larger context that goes beyond the power play of “a few bad apples” and the pornographic impressions these snapshots gave us when they first surfaced.

Each image alludes to a historic aspect of American history and the unresolved issues that can be traced to the civil war, racism, bigotry, and sexism. Each image is well-researched and documented, strategically titled, and each pixel counts for its special effects to create a mood and evoke a subtle nuance.

Rank and Defile (1 & 2) are clearly a reference to an officer who abuses his power and as a result defiles the honor of those who serve and betray the country they represent. Rank and Defile (1 & 2) recreates an unmistaken Goyesque mood to evoke the memory of Goya’s powerful and disturbing scenes of the brutal guerrilla war in the Peninsular War, scenes of horror, brutality, torture and the savagery of war.

Snapshot Heard ‘Round the World refers to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Concord Hymn, 1837 and relates to the start of the American Revolutionary War:

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled;

Here once the embattled farmers stood;

And fired the shot heard ’round the world.

In the Information Age, the silhouette of Satar Jabar, a prisoner at Abu Ghraib, has become an instant icon of the abuse scandal. Jabar was hooded, positioned on a box, and had wires attached to both hands and his penis and was told that he would be electrocuted if he fell off.

The image of this event was one of the most prominent to be featured in the media coverage of the scandal and frequently reappeared as a symbol of the torture and abuse. It became the most recognizable image worldwide, forcing the administration to reconsider policies and treatment of prisoners.

Basic Restraining, perhaps, cynically questions the basic training the men and women receive when they report to duty. Once again, this image belittles and humiliates the prisoner by restraining him to a bunk bed while he is stripped of clothes and his face disguised by a pair of ladies’ underwear.

Crucifiction (1 & 2) are not based on actual scenes from Abu Ghraib but on Fein’s reaction to his own observations of his restaging. One might wish the recreated images were fiction; however, these are reminders of the long history of torture that has its origins in the Roman Empire and has been part of every war. One can’t help but think of the confrontation between West and East, Christendom and Islam. The clash of civilizations is real and has been intensified since 9/11 and the occupation of Iraq by American forces.

Number Ten, in military speak, is the ultimate humiliation inflicted on the enemy. Here prisoners are ordered to face each other naked with the intent of violating the Islamic tradition of personal privacy. In this case, the officer is oblivious to such traditions and makes a mockery of such observance without realizing the damaging consequences of such irresponsible acts.

What’s so disturbing is not just violence but sexual violation — what is more, it’s sexual violation staged and captured on camera, made into a spectacle readily available for future and expanded viewing. On a scale of one to ten, this act is inflicting the highest grade of torture, for the violation borders on the sanctity of culture and religion.

In Downfall one senses the bankrupted morality of the Abu Ghraib command. It truly marks a watershed and a turning point in the “war against terrorism.”

In Trophy, the presence of the “onlooker” or “perpetrator” is so deliberate in his intent to humiliate and show us the helpless prisoner, his “trophy.” How disgraceful! Is the “Trophy” all the US military has to show the world? Is this in the country’s best interest? Does this represent our finest moment?

The whole experience of torture is so beyond our comprehension that it compelled Fein to place himself as a servicemember and penetrate the mindset of the perpetrators — an attempt to explore the pathology behind their acts and, in a sense, present the entire exhibition as his own trophy.

The whole Abu Ghraib fiasco is self-incriminating and stupid by all practical standards. Except that the idea of recording the acts of torture was, to a significant extent, the inspiration to commit them. Haven’t we seen this phenomenon before when the Nazis kept meticulous records of medical experiments, the Jewish loot of personal possessions and murder as a final solution?

In the Torture series, Fein succeeds in eliciting voyeurism and a morbid fascination with torture and points to humanity’s exploitative and dark side. He provokes all our senses to make us uneasy and question the practice of torture policies of this government. Torture is not just a concept; it’s a despicable act that achieves so little in advancing the US moral authority in the world or winning the war on terror. Thus the question is, is it ever justifiable?

The pictures originally circulated about Abu Ghraib prisoners reek of fraternity house hazing and gang initiation rituals. They encode racial hatred and fetishistic allusions to slavery and tell us that torture is not the mere application of pain to the task of extracting information.

Fein chooses to go the extra mile to give these crude snapshots an infusion of artistic expression, and by doing so, reminds us that art has another function and that it is not always about pretty and soothing pictures one finds in reverential museums and galleries and that great art can be unsettling.

The vision of Americans that emerges from Fein’s carefully crafted, nine-panel Abu Ghraib installation pierces into the heart of the scandal. Fein wants us to grasp the magnitude of a spectacle that stripped prisoners of their human dignity. The mocking of religion and treating prisoners of war as subhumans have become the face of America that won’t be forgotten by the estimated 1.6 million Muslims around the world.

In Torture, Fein has synthesized this unwieldy cache of evidence, producing an indispensable and riveting account of the Abu Ghraib nightmare. The compelling imagery fitted to human scale is in our face and deliberately provokes a visceral reaction, a moral stand, and perhaps a national discourse that might and can change the course. Can we let go of the belief that art can change the moral focus of our world?

In undertaking the Torture series, Fein joins the artistic giants like Francesco Goya and Pablo Picasso, who resorted to their artistic prowess to express the horrors of wars. Fein channels his artistic reservoir of explosive energy into a digital camera to expose the dark side of the first 21st-century war and its demoralizing and abhorrent effects. In a culture obsessed with violence, as indicative in Mel Gibson’s recent movies such as The Passion of Christ and Apocalypto, Fein’s Torture series, refashioned in an artistic rendition, warrants a serious look.

As much as Clinton Fein’s photographs in his show at Toomey-Tourell (49 Geary St, San Francisco) are about torture and politics, they are more captivatingly about reversing what we see imbedded in the images. Certainly Fein is drawing viewers into a political debate on the abuse of prisoners in the Iraqi prison, Abu Ghraib, by re-presenting those now infamous images first published in April 2004. However, by re-photographing them with stylized, hyper-real clarity Fein is giving the viewer permission to look at what was shunned in the originals: the details and the psychology revealed in them.

Fein furthers the idea that evidence of this atrocity is not only worth preserving (as the original captor-perpetrators did with their snapshots) but that it is also worth re-examining. Whether from image fatigue or short attention spans, Americans seem to have moved passed the initial horror invoked by the images three years ago. What Fein has effectively done is employ photography to critique the role of the original photographs. Whereas the original images were grainy and fuzzy, Fein’s images are sharp and precise, begging the question: which is more real? The viewer is left wondering. Number Ten, Fein’s re-staged version of a simulated sex act among hooded detainees elevates the sexualized undercurrent of torture by offering for inspection each detail in a way the original grainy and blurred photographs did not.

Number Ten, Fein’s re-staged version of a simulated sex act among hooded detainees elevates the sexualized undercurrent of torture by offering for inspection each detail in a way the original grainy and blurred photographs did not.

His use of stylized, dramatic lighting indeed amps up these perversions to bring that agenda to the forefront and draws our attention directly to it. He has intentionally conflated aesthetic experience with shocking imagery. One could argue that Fein has aestheticized the grotesque with this approach. One could also argue that he simply intended to present an uncensored version. However, his intention is as blurred as his images are sharp. After all, he did include fictionalized re-staged scenes in this exhibition. While these photographs are well realized, their presentation is not as carefully crafted as the images themselves. There are a few fairly obvious cut marks and some buckling and this, unfortunately, interferes with Fein’s well crafted aesthetic.

That said, there are many thought provoking questions raised by this exhibition and San Francisco is fortunate to have an ambitious gallery willing to mount it. Among those questions: is Clinton Fein appalled by the images he re-presents? Is he investigating the abuse of power? Is he dignifying the grotesque, making it allowable to view? In his statement, he addresses many issues in terms of using art as a social tool, however his images seem more layered with multiple meanings than he lets on. He leaves questions dangling, which is far more titillating than if he would have offered concrete answers.

Clinton Fein usually comes across as a political art guerrilla, putting images of elected officials and controversial figures in digitally manipulated, uncompromising positions (Rudy Giuliani in a urine-filled glass, President Bush on a crucifix, Saddam Hussein as an “I Want You” Uncle Sam), which immeditely freaks everybody out — especially the government. (His company’s Web site, www.annoy.com, features a fine chronicle of the dust-ups.) But the photos from the Abu Ghraib prison scandal gave him all he needed for his latest exhibit, “Torture.”

There are no loaded juxtapositions and no funny, morbid slogans, merely a faithful representation of the shocking photographs, blown up to mammoth size, which can leave you staggering about the gallery over the horror of it all.

His images, though, aren’t copies, and therein lies Fein’s fascinating take on the subject — the artist recreated the torture scenes using models. He stripped them naked, piled them into pyramids, smeared them with fluids (bodily?), and had them perform the same degrading acts as the prisoners. The resulting photographs are stylized, detailed, and enhanced by “fashion-photography lighting”; they carry, intentionally, a touch of the erotic (in contrast to the originals, Fein left the genitals exposed, giving a more thorough perspective to the scandal).

Fein is a natural at art that provokes and outrages, but he’s charted a new, compelling course with “Torture.”

Artist and provocateur Clinton Fein has been making incendiary political art for years (and setting legal precedent — he successfully sued Janet Reno in 1997 over applying indecency laws to Internet content) but nothing, he says, prepared him for making his current photo show, “Torture.”

He re-created the now familiar scenes of torture from Abu Ghraib prison. Seven of the images are based on photographs, and two are of scenes Fein imagined taking place. It was a jolting experience for the models and the artist. “In order to restage those images, you have to get in the mind-set of the people who were doing the torture,” Fein says. “People don’t fall into a pyramid, especially with hoods over their heads. The whole thing has been a learning process. After the first shoot, I felt physically sick. It was grueling and the place we were shooting in was grimy. It wasn’t a comfortable experience at all.”

Fein got the idea for the project after being interviewed by a researcher at Harvard University who was working on a book. She suggested that one reason Americans weren’t more disturbed by the Abu Ghraib scandal was that the images weren’t clear enough. They were taken by camera phone and reproduced at a low resolution.

“I thought about it. I gave a lot of other reasons why the images didn’t have the same impact as those from Vietnam — the 24-hour news cycle, for instance — but I thought that maybe if you saw them small, you don’t actually have to think about what they represent or what is really going on.”

So Fein made huge, high-resolution shots. As he worked, he found the process increasingly interesting. He filmed some of his models talking about how they felt about participating in torture scenes, which will be shown Saturday at an artist’s talk and posted on his Web site, www.clintonfein.com. In one shot, he even inserted himself in the frame.

“In one image from Abu Ghraib, the torturer is standing there with a smirk on his face. I did re- enact that one, and I put myself in it, since in many ways, it was the role I was playing,” he says. “It’s called ‘Trophy.’

“In many ways, all of these shots are like trophy shots, like images of lynchings in the South. It was another big realization I had that only came during the shoot, that all the images were staged as mine are. All of them draw on the concept of a trophy shot.”

Fein says that he became increasingly desensitized to the images he was creating as he staged more and more shoots, but he didn’t lose all sense of the horror. Both he and his models found themselves involved in the physicality of the situation — they complained of hurt knees, of the unpleasant weight of human bodies in the pyramid scenes — and that lesson isn’t lost on those who view the large-scale photographs either.

Like Stanley Milgram’s infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, in which college boys transformed themselves into warring prisoners and wardens with breathtaking speed, Fein’s photographs speak to the darker impulses of human nature, the power of context in determining behavior. There’s a lot of evidence that the Abu Ghraib soldiers were filling roles designed for them by their superiors.

But however repugnant a viewer might find Fein’s images, it’s important to understand the dimensions of torture. Although Fein has dealt with Abu Ghraib in previous shows, he says it’s a timely subject. “We have a new Congress being sworn in,” he says, “and this show is a reminder that if we do surge or accelerate military action in Iraq, we have to deal with what’s already happened. … We need policies to remedy that. If America is going to have any moral credibility, we have to look at what we’ve already done.”

Through Jan. 30. Artist-lead talk 6:30 p.m. Sat. Toomey-Tourell Gallery, 49 Geary St., S.F.

The Bigger Picture:’Torture’: Photographer restages infamous images from Abu Ghraib for new gallery show

By Reyhan Harmanci

January 11, 2007

Clinton Fein makes “art” out of Abu Ghraib. But this quick walk through hell is not so much about Abu Ghraib, nor about America’s insane megalomaniacal imprimatur, nor about dredging up yesterday’s news. It’s mainly about what happens to those friends and acquaintances of Fein who consent to help him re-enact these infamous episodes. You might think that since they know what they were getting into, it’s no big deal… or is it? If you’re not sure, Fein’s got some video you might wanna check out.

Suppose someone asked you to participate in such an exercise? Would you? Do you think it would be easy? And how about the original Iraqi unfortunates? How do you think they felt? How do you think they feel today? They had no choice, no inkling, no clue whether they’d be alive one moment and dead the next. Pick of First Thursday.

Clinton Fein – Torture

By Alan Bamburger

ArtBusiness.com

On January 4, 2007, at the Toomey Tourell Gallery in San Francisco, California, the latest exhibition by Clinton Fein, a controversial South African-born visual artist and writer, will be inaugurated.

It is already predicted that it will “reopen the wounds of Abu Ghraib.” Are those wounds closed for those who went through the terrifying prison established in Iraq by the American invaders, for the families of those victims, or for Humanity, which demands justice?

This is a group of photographic images—those taken by the torturing guards as part of their aberrant conduct—now digitally manipulated to transform them into works of artistic creation and, above all, denunciation, to the point that the press release states that they are “an impressive and challenging exploration of America’s approach to torture under the Bush administration.”

The alternative site Raw Story comments that it is through the diffuse, muted, and low-resolution transformation of the images that “vivid, strong, and terrifying reproductions” are achieved.

The works will be exhibited under the name “Torture,” it could not be any other, as the euphemism of mistreatment used by official statements and the press is not admissible when it is the infamous reality that the United States brought not only to Abu Ghraib. Those scenes of physical and psychological torture occurred equally or similarly in the concentration camp set up in the illegally occupied Guantanamo Naval Base, in other prisons in Iraq, in the Bagram prison (Afghanistan), and in the CIA’s secret prisons located in who knows how many truly dark places on the planet…

This is not the first time that Clinton Fein has ignited controversy, nor is it the first time he has addressed the issue of Abu Ghraib, which also has another pictorial display in the works of Colombian artist Fernando Botero. Fein focuses on the choreography and sexualization of torture, according to comments, as he has worked with images of naked prisoners forced into uncomfortable positions, compelled to simulate degrading and humiliating sexual acts. He delves into and exposes the dark side of a war detested, to which American citizens were led under deception, and in which tens of thousands of Iraqis have already been massacred.

The shock that Abu Ghraib represented in the consciousness of many, when the photos were published in April 2004, finds a necessary echo in “Torture” by Clinton Fein because it is essential for the wave of indignation to grow, powerful and systematically, to sweep away those who conceived, organized, and ordered the execution of the war against Iraq.

Images of Torture by US Military Featured at California Art Gallery

By Juana Carrasco Martin

Periodico 26, Cuba,

January 3, 2007

Clinton Fein’s exhibition, Torture, opened at Toomey Tourell Gallery in San Francisco in January 2007 as a shocking and defiant exploration of America’s approach to torture under the Bush administration.

A series of staged and digitally manipulated photographic images recreate the infamous torture scenes from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, transforming the diffuse, muted and low-resolution images into large-scale, vivid, powerful and frightening reproductions.