American Protest Literature by Zoe Trodd

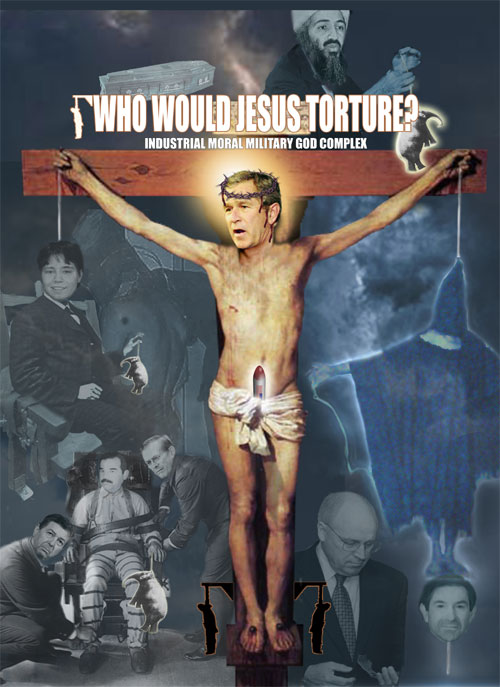

Clinton Fein - Who Would Jesus Torture

“What I am doing is the essence of what it means to be American,” explained the activist and artist Clinton Fein (b. 1964), in a recent interview; “America’s history is rich with people who went against the grain… dissent is the most powerful tool America has, and ensuring its protection is the most patriotic thing an American can do.” He’s part of a satiric protest tradition that extends from Philip Freneau to Doric Wilson. His photomontages are also part of a graphic-design protest tradition that includes ACT UP’s posters (cited by Fein as “unbelievably successful, smart, nimble, and creative”).

Fein, who was raised in South Africa under apartheid and came to America in 1986, battles for First Amendment rights. On January 30, 1997, he filed a lawsuit against Attorney General Janet Reno, challenging the constitutionality of the Communications Decency Act. Signed into law by Clinton in February 1996, this act made it a felony to communicate anything “indecent with the intent to annoy.” At the same time Fein launched his infamous website, Annoy.com. The case reached the Supreme Court, which decided that communications, even if intended to “annoy,” were protected by the Constitution. It was a landmark victory for First Amendment rights. But after 9/11, Fein felt alone in using those rights. “I was astounded at how few artists there were who were doing or say- ing anything even remotely political,” he said; “too many artists were deafeningly silent during a time when it would have been helpful for them to speak out.”

Fein resists the idea that “art and literature exist in a vacuum, and particularly that text is obligated to evoke pleasure.” Critiquing a culture of fear and the Bush administration’s “Shock and Awe” military policy, his art is calculated to shock. Technology is his weapon: he digitally alters images and subversively collages fragments, so that Condoleezza Rice becomes Marie Antoinette, Bin Laden the Statue of Liberty. The performance art of his continually published images parallel and challenge an amnesiac 24-hour news cycle, and he notes that the internet best accommodates contemporary protest: although anti- war protestors didn’t manage to stop the Iraq war, the Internet allowed them to mobilize huge demonstrations.

Fein resists the idea that “art and literature exist in a vacuum, and particularly that text is obligated to evoke pleasure.” Critiquing a culture of fear and the Bush administration’s “Shock and Awe” military policy, his art is calculated to shock. Technology is his weapon: he digitally alters images and subversively collages fragments, so that Condoleezza Rice becomes Marie Antoinette, Bin Laden the Statue of Liberty. The performance art of his continually published images parallel and challenge an amnesiac 24-hour news cycle, and he notes that the internet best accommodates contemporary protest: although anti- war protestors didn’t manage to stop the Iraq war, the Internet allowed them to mobilize huge demonstrations.

He believes that if the mainstream media were allowed to show what was really going on in Iraq, “America would be pulling out of there within a month, and Bush would be facing impeachment.” He watches the media deal with the legacy of the Vietnam war: the resistance to the word “quagmire”; the Pentagon’s refusal to allow images of returning coffins; the decision to “embed” journalists in Iraq, which Fein calls “the single most brilliant censorship strategy I have ever seen.” In 2004 Fein himself faced censorship when a printing company destroyed two of his images days before an exhibition opening. One, reproduced here, was “Who Would Jesus Torture?,” which the company felt would offend Christians.

It pictures President Bush with a missile as his phallus, recalling Maj. T. J. “King” Kong straddling a missile at the end of the movie Dr. Strangelove (1964). In the background is an Abu Ghraib image of a prisoner receiving a simulated blowjob: Fein used this “to add the sexual dimension that seemed to be glaringly obvious in the Abu Ghraib imagery- the elephant in the room.” The elephants in the image represent three notions: a refusal to state the obvious; Republicans; and a circus elephant who killed her trainer in 1916. Attempts to electrocute or shoot her failed, and she was hung. Fein’s image comments further on the death penalty: Lynndie England, the soldier punished for her role in the incident, sits on an electric chair, and Donald Rumsfeld and John Ashcroft strap Saddam Hussein into another. This asks, Fein says, “how exactly America thinks it retains the moral highroad to even condemn the torture being perpetrated in its name, when it still executes people.” The outstretched arm of an Iraqi, from another Abu Ghraib image, pro- vides the question Bush is trying to balance, which Fein formulates as: “Would killing Lynndie England and Saddam Hussein equal the damage wrought by the torturing of the Iraqis by both Saddam Hussein and the Americans?”

The crucifixion imagery echoes Nick Ut’s famous photograph “Napalm” (1972). Fein echoed that photograph to debunk the idea that one kind of violence is worse than another: “Whether you’re running naked screaming with napalm covering your body, or being forced to climb onto a human pyramid of naked prisoners, all represent violence. There’s no screaming of ‘baby killers’ at active duty service members, yet babies have hardly been spared the horror of tons of depleted uranium dumped on them.” Struck by the lack of outraged public response to the Abu Ghraib images, he concluded that a “combination of communications allowing instant gratification, collective attention deficit disorder, information glut, and an unwillingness to confront who we are in those grainy photos, all combined to defuse their impact.” So he tried to make the im- ages into something that might rival the protest art of the Vietnam war.

About Zoe Trodd

Professor Zoe Trodd is Director of the Rights Lab at the University of Nottingham, the world’s largest and leading group of modern slavery scholars and university Beacon of Excellence that is delivering research to help end global slavery by 2030. Her research focus is strategies for ending slavery.

She has a PhD and MA from Harvard University and a BA from the University of Cambridge. Before joining Nottingham as a professor in 2012, she taught at Columbia University.

She is a member of the AHRC’s Peer Review College and GCRF Strategic Advisory Group; a member of the board of Historians Against Slavery; and a Newnham College (University of Cambridge) Associate. She edits a book series for Cambridge University Press called Slaveries Since Emancipation and teaches a massive open online course (MOOC) called Ending Slavery.