Art of Engagement by Peter Selz

Against War and Violence

Like Forkscrew Graphics, Clinton Fein (b. 1964) has used the iconic image of the hooded prisoner, multiplying it fifty times to stand in for the stars in the American flag in his print Like Apple Fucking Pie (2004). The flag’s stripes are replaced with the official text of the Abu Ghraib report, in red ink between white intervals. This image, along with another by Fein, was shredded and destroyed by a high-tech Sil- icon Valley printing firm, which claimed the work violated company policy against depicting torture and disparaging religion. Fein is no stranger to censorship. Earlier, he established a provocative website, www .annoy.com, in response to the 1996 Communications Decency Act, which made it illegal to send “indecent” communications over the Internet. He went so far as to sue Attorney General Janet Reno over the law, winning a partial victory in the U.S. Supreme Court in 1999.

Born in Johannesburg, where he witnessed the effects of apartheid, Fein studied industrial psychology before moving to Los Angeles in the mid-1980s and later settling in San Francisco. His art ranges over a variety of political issues, from urban blight to the masochistic and homoerotic implications of life in the military to the ongoing “war on terror” and erosion of American civil liberties. A 2004 exhibit in San Francisco was explicitly intended to make viewers aware of the “nightmarish rollbacks of the Constitution by an Administration that has done more to kill civil liberties than Osama bin Laden could ever have wished for in his wettest dreams.”4”

Born in Johannesburg, where he witnessed the effects of apartheid, Fein studied industrial psychology before moving to Los Angeles in the mid-1980s and later settling in San Francisco. His art ranges over a variety of political issues, from urban blight to the masochistic and homoerotic implications of life in the military to the ongoing “war on terror” and erosion of American civil liberties. A 2004 exhibit in San Francisco was explicitly intended to make viewers aware of the “nightmarish rollbacks of the Constitution by an Administration that has done more to kill civil liberties than Osama bin Laden could ever have wished for in his wettest dreams.”4”

Typical of Fein’s ongoing attack on the Bush administration’s policies is a 2001 photocollage titled Blood-Spangled Banner. Here bin Laden’s head replaces that of Miss Liberty, while the right arm of the statue holds Bush’s dismembered head aloft, instead of the great torch of freedom. The work is accompanied by a verse that begins:

Oh, say can you feel

by the dusk’s fading light

How so sadly we mourn

our constitution is screaming?

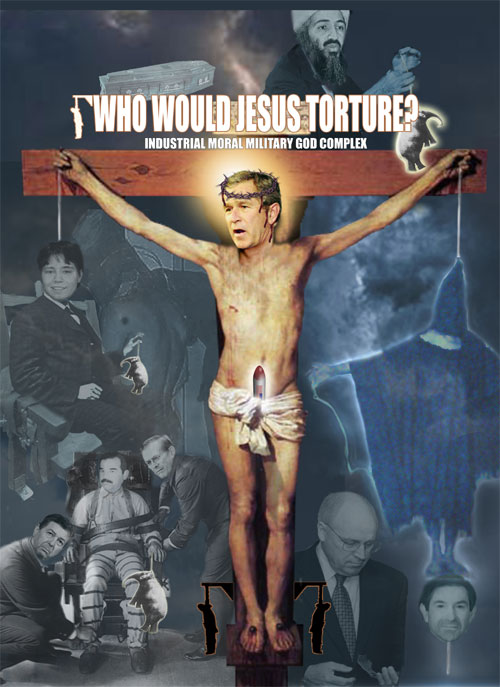

In another image, titled Better Be the Last (2004) and modeled on Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, Fein shows the president and his cronies seated around a table with almost no food left on it. Continuing the religious theme, the digital print Who Would Jesus Torture? (2004) depicts Bush on the cross in place of the Savior. (The original version of this image was also destroyed by the printer.) A phallic missile, equipped with the American flag, emerges from Bush’s loin- cloth. Bin Laden sits above. From one arm of the cross hangs the icon of the hooded man, while below the other arm, on an electric chair, sits Private Lindy English, the soldier photographed “taming” naked prisoners with a dog leash. Below English, we see John Ashcroft and Donald Rumsfeld strapping Saddam Hussein to a chair, while Dick Cheney and Paul Wolfowitz (the chief architect of the Iraq invasion) appear on the lower right. Several of these figures dangle toy elephants-alluding not only to the Republican Party logo but also to Thomas Edison’s demonstration of the strength of the electric chair (his own invention, though this fact is rarely mentioned) by shocking an elephant to death. Who invented this torture? we might also ask.

Peter Selz, an Art Museum Force on Two Coasts, Dies at 100 (New York Times)

Peter Selz, who as a leading curator at the Museum of Modern Art staged wide-ranging exhibitions of Mark Rothko’s paintings and Auguste Rodin’s sculptures before leaving to become the founding director of the University Art Museum, Berkeley, died on June 21 in Albany, Calif. He was 100.

His daughter Gabrielle Selz confirmed the death, at an assisted living facility. He had lived in a Modernist house in Berkeley for more than 50 years before recently moving to nearby Albany.

Mr. Selz, a German-born bon vivant whose guests at his Manhattan apartment often included the artists Franz Kline, Helen Frankenthaler and her husband, Robert Motherwell, as well as Rothko, joined MoMA in 1958 as its curator of painting and sculpture exhibitions, one of the most prestigious positions in the art world.

“New Images of Man” (1959), Mr. Selz’s first major show at MoMA, was a haunting, largely despairing survey of the human image through paintings and sculptures by 23 American and European artists, including Francis Bacon, Jackson Pollock, Jean Dubuffet and Alberto Giacometti.

When he announced the show, Mr. Selz described its 104 postwar works as “effigies of the disquiet man.”

The reviews were mixed, which Mr. Selz attributed largely to the exhibition’s devotion to figurative works and not to Abstract Expressionism, the popular movement of the era. But in her review in The New York Times, the critic Aline B. Saarinen wrote that many of the paintings and sculptures were “powerful mirrors of some of the significant aspects of the human condition in our time.”

By Richard Sandomir

June 28, 2019

Buy the Art of Engagement

Art of Engagement

Visual Politics in California and Beyond

by Peter Selz (Author), Susan Landauer (Contributor)

January 2006

First Edition